Epicureanism

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

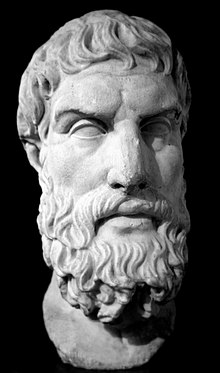

is a system of

philosophy based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher

Epicurus, founded around 307 BC. Epicurus was an

atomic materialist, following in the steps of

Democritus. His materialism led him to a

general attack on superstition and divine intervention. Following

Aristippus—about whom very little is known—Epicurus believed that what he called "pleasure" is the greatest good, but the way to attain such pleasure is to live modestly and to gain knowledge of the workings of the world and the limits of one's desires. This led one to attain a state of tranquility (

ataraxia) and freedom from fear, as well as absence of bodily pain (

aponia). The combination of these two states is supposed to constitute happiness in its highest form. Although Epicureanism is a form of

hedonism, insofar as it declares pleasure to be the sole intrinsic good, its conception of absence of pain as the greatest pleasure and its advocacy of a simple life makes it different from "hedonism" as it is commonly understood.

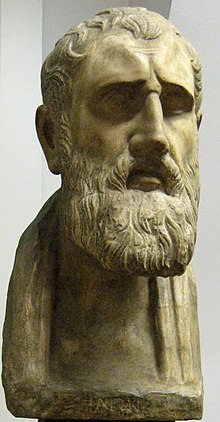

Epicureanism was originally a challenge to

Platonism, though later it became the main opponent of

Stoicism. Epicurus and his followers shunned politics. After the death of Epicurus, his school was headed by

Hermarchus; later many Epicurean societies flourished in the Late Hellenistic era and during the Roman era (such as those in

Antiochia,

Alexandria,

Rhodes, and

Ercolano). Its best-known Roman proponent was the poet

Lucretius. By the end of the Roman Empire, being opposed by philosophies (mainly Neo-Platonism) that were now in the ascendance, Epicureanism had all but died out, and would be resurrected in the 17th century by the atomist

Pierre Gassendi, who adapted it to the Christian doctrine.

Some writings by Epicurus have survived. Some scholars consider the epic poem

On the Nature of Things by

Lucretius to present in one unified work the core arguments and theories of Epicureanism. Many of the papyrus scrolls unearthed at the

Villa of the Papyri at

Herculaneum are Epicurean texts. At least some are thought to have belonged to the Epicurean

Philodemus.

History

The school of

Epicurus, called "The Garden," was based in Epicurus' home and garden. It had a small but devoted following in his lifetime. Its members included

Hermarchus,

Idomeneus,

Colotes,

Polyaenus, and

Metrodorus. Epicurus emphasized friendship as an important ingredient of happiness, and the school seems to have been a moderately ascetic community which rejected the political limelight of Athenian philosophy. They were fairly cosmopolitan by Athenian standards, including women and slaves. Some members were also

vegetarians as Epicurus did not eat meat, although no prohibition against eating meat was made.

[1][2]The school's popularity grew and it became, along with

Stoicism and

Skepticism, one of the three dominant schools of Hellenistic Philosophy, lasting strongly through the later

Roman Empire.

[3] Another major source of information is the Roman politician and philosopher

Cicero, although he was highly critical, denouncing the Epicureans as unbridled

hedonists, devoid of a sense of virtue and duty, and guilty of withdrawing from public life. Another ancient source is

Diogenes of Oenoanda, who composed a large inscription at

Oenoanda in

Lycia.

A library in the

Villa of the Papyri, in

Herculaneum, was perhaps owned by

Julius Caesar's father-in-law,

Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus. The

scrolls which the library consisted of were preserved albeit in carbonized form by the eruption of

Vesuvius in 79 AD. Several of these

Herculaneum papyri which are unrolled and deciphered were found to contain a large number of works by

Philodemus, a late Hellenistic Epicurean, and Epicurus himself, attesting to the school's enduring popularity. The task of unrolling and deciphering the over 1800 charred

papyrus scrolls continues today.

With the dominance of the Neo-Platonism and

Peripatetic School philosophy (and later Christianity), Epicureanism declined. By the late third century AD, there was very little trace of its existence.

[4]The early Christian writer

Lactantius criticizes Epicurus at several points throughout his

Divine Institutes. In

Dante's

Divine Comedy, the Epicureans are depicted as

heretics suffering in the sixth circle of

hell. In fact, Epicurus appears to represent the ultimate heresy. The word for a

heretic in the

Talmudic literature is "Apiqoros" (אפיקורוס).

By the 16th century, the works of

Diogenes Laertius were being printed in Europe. In the 17th century the French Franciscan priest, scientist and philosopher

Pierre Gassendi wrote two books forcefully reviving Epicureanism. Shortly thereafter, and clearly influenced by Gassendi,

Walter Charleton published several works on Epicureanism in English. Attacks by Christians continued, most forcefully by the

Cambridge Platonists.

In the

Modern Age, scientists adopted

atomist theories, while

materialist philosophers embraced Epicurus' hedonist ethics and restated his objections to natural

teleology.

Religion

Epicureanism emphasizes the neutrality of the gods, that they do not interfere with human lives. It states that gods, matter, and souls are all made up of

atoms. Souls are made from atoms, and gods possess souls, but their souls adhere to their bodies without escaping. Humans have the same kind of souls, but the forces binding human atoms together do not hold the soul forever. The Epicureans also used the

atomist theories of

Democritus and

Leucippus to assert that man has free will. They held that all thoughts are merely atoms swerving randomly.

The

Riddle of Epicurus, or

Problem of evil, is a famous argument against the existence of an all-powerful and providential God or gods. As recorded by

Lactantius:

God either wants to eliminate bad things and cannot, or can but does not want to, or neither wishes to nor can, or both wants to and can. If he wants to and cannot, then he is weak – and this does not apply to god. If he can but does not want to, then he is spiteful – which is equally foreign to god's nature. If he neither wants to nor can, he is both weak and spiteful, and so not a god. If he wants to and can, which is the only thing fitting for a god, where then do bad things come from? Or why does he not eliminate them?

— Lactantius, De Ira Deorum[5]

This type of

trilemma argument (God is omnipotent, God is good, but Evil exists) was one favoured by the ancient Greek

skeptics, and this argument may have been wrongly attributed to Epicurus by Lactantius, who, from his

Christian perspective, regarded Epicurus as an

atheist.

[6] According to

Reinhold F. Glei, it is settled that the argument of theodicy is from an academical source which is not only not Epicurean, but even anti-Epicurean.

[7] The earliest extant version of this

trilemma appears in the writings of the skeptic

Sextus Empiricus.

[8]Epicurus' view was that there were gods, but that they were neither willing nor able to prevent evil. This was not because they were malevolent, but because they lived in a perfect state of

ataraxia, a state everyone should strive to emulate; it is not the gods who are upset by evils, but people.

[6] Epicurus conceived the gods as blissful and immortal yet material beings made of atoms inhabiting the

metakosmia: empty spaces between worlds in the vastness of infinite space. In spite of his recognition of the gods, the practical effect of this materialistic explanation of the gods' existence and their complete non-intervention in human affairs renders his philosophy akin in divine effects to the attitude of

Deism.

In Dante's

Divine Comedy, the flaming tombs of the Epicureans are located within the sixth circle of hell (

Inferno, Canto X). They are the first heretics seen and appear to represent the ultimate, if not quintessential, heresy.

[9] Similarly, according to Jewish

Mishnah, Epicureans (

apiqorsim, people who share the beliefs of the movement) are among the people who do not have a share of the "World-to-Come" (afterlife or the world of the

Messianic era).

Parallels may be drawn to

Buddhism, which similarly emphasizes a lack of divine interference and aspects of its

atomism. Buddhism also resembles Epicureanism in its temperateness, including the belief that great excess leads to great dissatisfaction.

Philosophy

The philosophy originated by Epicurus flourished for seven centuries. It propounded an ethic of individual

pleasure as the sole or chief good in life. Hence, Epicurus advocated living in such a way as to derive the greatest amount of pleasure possible during one's lifetime, yet doing so moderately in order to avoid the suffering incurred by overindulgence in such pleasure. The emphasis was placed on pleasures of the mind rather than on physical pleasures. Therefore, according to Epicurus, with whom a person eats is of greater importance than what is eaten. Unnecessary and, especially, artificially produced desires were to be suppressed. Since learning,

culture, and civilization as well as social and political involvements could give rise to desires that are difficult to satisfy and thus result in disturbing one's peace of mind, they were discouraged. Knowledge was sought only to rid oneself of religious fears and superstitions, the two primary fears to be eliminated being fear of the gods and of death. Viewing marriage and what attends it as a threat to one's peace of mind, Epicurus lived a celibate life but did not impose this restriction on his followers.

The philosophy was characterized by an absence of divine principle. Lawbreaking was counseled against because of both the shame associated with detection and the punishment it might bring. Living in fear of being found out or punished would take away from pleasure, and this made even secret wrongdoing inadvisable. To the Epicureans, virtue in itself had no value and was beneficial only when it served as a means to gain happiness. Reciprocity was recommended, not because it was divinely ordered or innately noble, but because it was personally beneficial. Friendships rested on the same mutual basis, that is, the pleasure resulting to the possessors. Epicurus laid great emphasis on developing friendships as the basis of a satisfying life.

of all the things which wisdom has contrived which contribute to a blessed life, none is more important, more fruitful, than friendship

While the pursuit of pleasure formed the focal point of the philosophy, this was largely directed to the "static pleasures" of minimizing pain, anxiety and suffering. In fact, Epicurus referred to life as a "bitter gift".

When we say . . . that pleasure is the end and aim, we do not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or the pleasures of sensuality, as we are understood to do by some through ignorance, prejudice or wilful misrepresentation. By pleasure we mean the absence of pain in the body and of trouble in the soul. It is not by an unbroken succession of drinking bouts and of revelry, not by sexual lust, nor the enjoyment of fish and other delicacies of a luxurious table, which produce a pleasant life; it is sober reasoning, searching out the grounds of every choice and avoidance, and banishing those beliefs through which the greatest tumults take possession of the soul.

— Epicurus, "Letter to Menoeceus"[11]

The Epicureans believed in the existence of the gods, but believed that the gods were made of atoms just like everything else. It was thought that the gods were too far away from the earth to have any interest in what man was doing; so it did not do any good to pray or to sacrifice to them. The gods, they believed, did not create the universe, nor did they inflict punishment or bestow blessings on anyone, but they were supremely happy; this was the goal to strive for during one's own human life.

"

Live unknown was one of [key] maxims. This was completely at odds with all previous ideas of seeking fame and glory, or even wanting something so apparently decent as honor."

[12]Epicureanism rejects immortality and mysticism; it believes in the soul, but suggests that the soul is as mortal as the body. Epicurus rejected any possibility of an afterlife, while still contending that one need not fear death: "Death is nothing to us; for that which is dissolved, is without sensation, and that which lacks sensation is nothing to us."

[13] From this doctrine arose the Epicurean Epitaph:

Non fui, fui, non sum, non curo ("I was not; I was; I am not; I do not care"), which is inscribed on the gravestones of his followers and seen on many ancient gravestones of the

Roman Empire. This quotation is often used today at

humanist funerals.

[14]Ethics

Epicurus was an early thinker to develop the notion of justice as a social contract. He defined justice as an agreement "neither to harm nor be harmed". The point of living in a society with laws and punishments is to be protected from harm so that one is free to pursue happiness. Because of this, laws that do not contribute to promoting human happiness are not just. He gave his own unique version of the

Ethic of Reciprocity, which differs from other formulations by emphasizing minimizing harm and maximizing happiness for oneself and others:

It is impossible to live a pleasant life without living wisely and well and justly (agreeing "neither to harm nor be harmed"[15]),

and it is impossible to live wisely and well and justly without living a pleasant life.[16]

Epicureanism incorporated a relatively full account of the

social contract theory, following after a vague description of such a society in

Plato's

Republic. The social contract theory established by Epicureanism is based on mutual agreement, not divine decree.

The human soul is mortal because, like everything, it is composed of atoms, but made up the most perfect, rounded and smooth. It disappears with the destruction of the body. We don't have to fear death because, firstly, nothing follows after the disappearance of the body, and, secondly, the experience of death is not so: "the most terrible evil, death, is nothing for us, since when we exist, death does not exist, and when death exists, we do not exist "(Epicurus," Letter to Menoeceus ").

Nature has set a target of every actions of living beings (including men) seeking pleasure, as shown by the fact that children instinctively and animals tend to shy away from pleasure and pain. Pleasure and pain are the main reasons for each actions of living beings. Pure pleasure is the highest good, pain the supreme evil.

The pleasures and pains are the result of the realization or impairment of appetites. Epicurus distinguishes three kinds of appetites:

- Natural and necessary: eating, drinking, sleeping; They are easy to please.

- Natural but not necessary: as the erotic; they are not difficult to master and are not needed for happiness.

- Those who are not natural nor necessary: we must reject them completely.

Types of pleasures: since man is composed of body and soul there are two general types of pleasures:

- Pleasures of the body: Although considered to be the most important, in the background the proposal is to give up these pleasures and seek the lack of body pain. There are soul aches and pains of the body, but the body is bad because the pain of the soul is directly or indirectly related to body aches occurring in the present or to anticipations of future pains. Epicurus believed there was no need to fear bodily pain because when it is intense and unbearable, it is also usually shorter. When it lasts longer and is less intense, it is more bearable. He also believed one should relieve physical pain with the memory of past joys, and in extreme cases, to suicide.

- Pleasures of the soul: the pleasure of the soul is greater than the pleasure of the body: pleasures of the body are effective in the present, but those of the soul are more durable; the pleasures of the soul, Epicurus believed, can eliminate or reduce bodily pains or displeasures.

Epicurean physics

Epicurus' philosophy of the physical world is found in his

Letter to Herodotus: Diogenes Laertius 10.34–83.

If the sum of all matter ("the totality") was limited and existed within an unlimited void, it would be scattered and constantly becoming more diffuse, because the finite collection of bodies would travel forever, having no obstacles. Conversely, if the totality was unlimited it could not exist within a limited void, for the unlimited bodies would not all have a place to be in. Therefore, either both the void and the totality must be limited or both must be unlimited and – as is mentioned later – the totality is unlimited (and therefore so is the void).

Forms can change, but not their inherent qualities, for change can only affect their shape. Some things can be changed and some things cannot be changed because forms that are unchangeable cannot be destroyed if certain attributes can be removed; for attributes not only have the intention of altering an unchangeable form, but also the inevitable possibility of becoming—in relation to the form's disposition to its present environment—both an armor and a vulnerability to its stability.

Further proof that there are unchangeable forms and their inability to be destroyed, is the concept of the "non-evident." A form cannot come into being from the void—which is nothing; it would be as if all forms come into being spontaneously, needless of reproduction. The implied meaning of "destroying" something is to undo its existence, to make it not there anymore, and this cannot be so: if the void is that which does not exist, and if this void is the implied destination of the destroyed, then the thing in reality cannot be destroyed, for the thing (and all things) could not have existed in the first place (as

Parmenides said,

ex nihilo nihil fit: nothing comes from nothing). This totality of forms is eternal and unchangeable.

Atoms move, in the appropriate way, constantly and for all time. Forms first come to us in images or "projections"—outlines of their true selves. For an image to be perceived by the human eye, the "atoms" of the image must cross a great distance at enormous speed and must not encounter any conflicting atoms along the way. The presence of atomic resistance equal atomic slowness; whereas, if the path is deficient of atomic resistance, the traversal rate is much faster (and clearer). Because of resistance, forms must be unlimited (unchangeable and able to grasp any point within the void) because, if they weren't, a form's image would not come from a single place, but fragmented and from several places. This confirms that a single form cannot be at multiple places at the same time.

Epicurus for the most part follows Democritean atomism but differs in proclaiming the

clinamen (swerve or declination). Imagining atoms to be moving under an external force, Epicurus conceives an occasional atom "swerving" for reasons peculiar to itself, i.e. not by external compulsion but by "free will". In this, his view absolutely opposes Democritean determinism as well as developed Stoicism. Otherwise he conceives of atoms as does Democritus – in that they have position, number, and shape. To Democritus' differentiating criteria, Epicurus adds "weight", but maintains Democritus' view that atoms are necessarily indivisible and hence possess no demonstrable

internal space.

And the senses warrant us other means of perception: hearing and smelling. As in the same way an image traverses through the air, the atoms of sound and smell traverse the same way. This perceptive experience is itself the flow of the moving atoms; and like the changeable and unchangeable forms, the form from which the flow traverses is shed and shattered into even smaller atoms, atoms of which still represent the original form, but they are slightly disconnected and of diverse magnitudes. This flow, like that of an echo, reverberates (off one's senses) and goes back to its start; meaning, one's sensory perception happens in the coming, going, or arch, of the flow; and when the flow retreats back to its starting position, the atomic image is back together again: thus when one smells something one has the ability to see it too [because atoms reach the one who smells or sees from the object.]

And this leads to the question of how atomic speed and motion works. Epicurus says that there are two kinds of motion: the straight motion and the curved motion, and its motion traverse as fast as the speed of thought.

Epicurus proposed the idea of 'the space between worlds' (

metakosmia) the relatively empty spaces in the infinite void where worlds had not been formed by the joining together of the

atoms through their endless motion.

Epistemology

Epicurean

epistemology has three criteria of

truth: sensations (

aisthêsis), preconceptions (

prolepsis), and feelings (

pathê).

Prolepsis is sometimes translated as "basic grasp" but could also be described as "universal ideas": concepts that are understood by all. An example of

prolepsis is the word "man" because every person has a preconceived notion of what a man is. Sensations or sense perception is knowledge that is received from the senses alone. Much like modern science, Epicurean philosophy posits that

empiricism can be used to sort truth from falsehood. Feelings are more related to ethics than Epicurean

physical theory. Feelings merely tell the individual what brings about pleasure and what brings about pain. This is important for the Epicurean because these are the basis for the entire Epicurean ethical doctrine.

According to Epicurus, the basic means for our understanding of things are the "sensations" (

aestheses), "concepts" (

prolepsis), "emotions" (

pathe), and the "focusing of thought into an impression" (

phantastikes epiboles tes dianoias).

Epicureans reject

dialectic as confusing (

parelkousa) because for the physical philosophers it is sufficient to use the correct words which refer to the concepts of the world. Epicurus then, in his work

On the Canon, says that the criteria of truth are the senses, the preconceptions and the feelings. Epicureans add to these the focusing of thought into an impression. He himself is referring to those in his

Epitome to Herodotus and in

Principal Doctrines.

[17]The

senses are the first criterion of truth, since they create the first impressions and testify the existence of the external world. Sensory input is neither subjective nor deceitful, but the misunderstanding comes when the mind adds to or subtracts something from these impressions through our preconceived notions. Therefore, our sensory input alone cannot lead us to inaccuracy, only the concepts and opinions that come from our

interpretations of our sensory input can. Therefore, our sensory data is the only truly accurate thing which we have to rely for our understanding of the world around us.

And whatever image we receive by direct understanding by our mind or through our sensory organs of the shape or the essential properties that are the true form of the solid object, since it is created by the constant repetition of the image or the impression it has left behind. There is always inaccuracy and error involved in bringing into a judgment an element that is additional to sensory impressions, either to confirm [what we sensed] or deny it.

— Letter to Herodotus, 50

Epicurus said that all the tangible things are real and each impression comes from existing objects and is determined by the object that causes the sensations.

Therefore all the impressions are real, while the preconceived notions are not real and can be modified.

— Sextus Empiricus, To Rationals, 7.206–45

If you battle with all your sensations, you will be unable to form a standard for judging which of them are incorrect.

— Principal Doctrines, 23

The

concepts are the categories which have formed mentally according to our sensory input, for example the concepts "man", "warm", and "sweet", etc. These concepts are directly related to memory and can be recalled at any time, only by the use of the respective word. (Compare the

anthropological Sapir–Whorf hypothesis). Epicurus also calls them "the meanings that underlie the words" (

hypotetagmena tois phthongois: semantic substance of the words) in his letter to Herodotus. The

feelings or

emotions (

pathe) are related to the senses and the concepts. They are the inner impulses that make us feel like or dislike about certain external objects, which we perceive through the senses, and are associated with the preconceptions that are recalled.

In this moment that the word "man" is spoken, immediately due to the concept [or category of the idea] an image is projected in the mind which is related to the sensory input data.

— Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, X, 33

First of all Herodotus, we must understand the meanings that underlie the words, so that by referring to them, we may be able to reach judgments about our opinions, matters of inquiry, or problems and leave everything undecided as we can argue endlessly or use words that have no clearly defined meaning.

— Letter to Herodotus, 37

Apart from these there is the

assumption (

hypolepsis), which is either the hypothesis or the opinion about something (matter or action), and which can be correct or incorrect. The assumptions are created by our sensations, concepts and emotions. Since they are produced automatically without any rational analysis and verification (see the modern idea of the

subconscious) of whether they are correct or not, they need to be confirmed (

epimarteresis: confirmation), a process which must follow each assumption.

For beliefs they [the Epicureans] use the word hypolepsis which they claim can be correct or incorrect.

— Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, X, 34

Referring to the "focusing of thought into an impression" or else "intuitive understandings of the mind", they are the impressions made on the mind that come from our sensations, concepts and emotions and form the basis of our assumptions and beliefs. All this unity (sensation – concept or category – emotion – focusing of thought into an impression) leads to the formation of a certain assumption or belief (

hypolepsis). (Compare the modern

anthropological concept of a "

world view".) Following the lead of

Aristotle, Epicurus also refers to impressions in the form of mental images which are projected on the mind. The "correct use of impressions" was something adopted later by the

Stoics.

Our assumptions and beliefs have to be 'confirmed', which actually proves if our opinions are either accurate or inaccurate. This verification and confirmation (

epimarteresis) can only be done by means of the "evident reason" (henargeia), which means what is self-evident and obvious through our sensory input.

An example is when we see somebody approaching us, first through the sense of eyesight, we perceive that an object is coming closer to us, then through our preconceptions we understand that it is a human being, afterwards through that assumption we can recognize that he is someone we know, for example Theaetetus. This assumption is associated with pleasant or unpleasant emotions accompanied by the respective mental images and impressions (the focusing of our thoughts into an impression), which are related to our feelings toward each other. When he gets close to us, we can confirm (verify) that he is Socrates and not Theaetetus through the proof of our eyesight. Therefore, we have to use the same method to understand everything, even things which are not observable and obvious (adela, imperceptible), that is to say the confirmation through the evident reason (

henargeia). In the same way we have to reduce (

reductionism) each assumption and belief to something that can be proved through the self-evident reason (empirically verified).

Verification theory and

reductionism have been adopted, as we know, by the modern

philosophy of science. In this way, one can get rid of the incorrect assumptions and beliefs (

biases) and finally settle on the real (confirmed) facts.

Consequently the confirmation and lack of disagreement is the criterion of accuracy of something, while non-confirmation and disagreement is the criterion of its inaccuracy. The basis and foundation of [understanding] everything are the obvious and self-evident [facts].

— Sextus Empiricus, To Rationals, 7.211–6

All the above-mentioned criteria of knowledge form the basic principles of the [scientific] method, that Epicurus followed in order to find the truth. He described this method in his work

On the Canon or

On the Criteria.

If you reject any sensation and you do not distinguish between the opinion based on what awaits confirmation and evidence already available based on the senses, the feelings and every intuitive faculty of the mind, you will send the remaining sensations into a turmoil with your foolish opinions, thus getting rid of every standard for judging. And if among the perceptions based on beliefs are things that are verified and things that are not, you are guaranteed to be in error since you have kept everything that leads to uncertainty concerning the correct and incorrect.[18]

(Based on excerpt from Epicurus' Gnoseology

Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments, Nikolaos Bakalis, Trafford Publishing 2005,

ISBN 1-4120-4843-5)

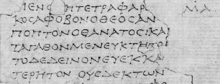

Tetrapharmakos

Main article:

TetrapharmakosPart of Herculaneum Papyrus 1005 (P.Herc.1005), col. 5. Contains Epicurean tetrapharmakos from Philodemus' Adversus Sophistas.

Tetrapharmakos, or "The four-part cure", is Epicurus' basic guideline as to how to live the happiest possible life. This poetic doctrine was handed down by an anonymous Epicurean who summed up Epicurus' philosophy on happiness in four simple lines:

Don't fear god,

Don't worry about death;

What is good is easy to get, and

What is terrible is easy to endure.

Notable Epicureans

One of the earliest

Roman writers espousing Epicureanism was

Amafinius. Other adherents to the teachings of Epicurus included the poet

Horace, whose famous statement

Carpe Diem ("Seize the Day") illustrates the philosophy, as well as

Lucretius, as he showed in his

De Rerum Natura. The poet

Virgil was another prominent Epicurean (see

Lucretius for further details). The Epicurean philosopher

Philodemus of Gadara, until the 18th century only known as a poet of minor importance, rose to prominence as most of his work along with other Epicurean material was discovered in the

Villa of the Papyri.

Julius Caesar leaned considerably toward Epicureanism, which e.g. led to his plea against the death sentence during the trial against

Catiline, during the

Catiline conspiracy where he spoke out against the

Stoic Cato.

[19]In modern times

Thomas Jefferson referred to himself as an Epicurean.

[20] Other modern-day Epicureans were

Gassendi,

Walter Charleton,

François Bernier,

Saint-Evremond,

Ninon de l'Enclos,

Denis Diderot,

Frances Wright and

Jeremy Bentham.

Christopher Hitchens referred to himself as an Epicurean.

[21] In France, where perfumer/restaurateur Gérald Ghislain refers to himself as an Epicurean,

[22] Michel Onfray is developing a

post-modern approach to Epicureanism.

[23] In his recent book titled

The Swerve,

Stephen Greenblatt identified himself as strongly sympathetic to Epicureanism and Lucretius.

Modern usage and misconceptions

In modern popular usage, an

epicurean is a connoisseur of the arts of life and the refinements of sensual pleasures;

epicureanism implies a love or knowledgeable enjoyment especially of good food and drink—see the definition of

gourmet at

Wiktionary.

Because Epicureanism posits that pleasure is the ultimate good (telos), it has been commonly misunderstood since ancient times as a doctrine that advocates the partaking in fleeting pleasures such as constant partying, sexual excess and decadent food. This is not the case. Epicurus regarded

ataraxia (tranquility, freedom from fear) and

aponia (absence of pain) as the height of happiness. He also considered prudence an important virtue and perceived excess and overindulgence to be contrary to the attainment of ataraxia and aponia.

[11]See also

Notes

The Hidden History of Greco-Roman Vegetarianism

The Philosophy of Vegetarianism – Daniel A. Dombrowski

Erlend D. MacGillivray "The Popularity of Epicureanism in Late-Republic Roman Society" The Ancient World, XLIII (2012) 151–72.

Michael Frede, Epilogue, The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy pp. 795–96;

Lactantius, De Ira Deorum, 13.19 (Epicurus, Frag. 374, Usener). David Hume paraphrased this passage in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion: "EPICURUS's old questions are yet unanswered. Is he willing to prevent evil, but not able? then is he impotent. Is he able, but not willing? then is he malevolent. Is he both able and willing? whence then is evil?"

Mark Joseph Larrimore, (2001), The Problem of Evil, pp. xix-xxi. Wiley-Blackwell

Reinhold F. Glei, Et invidus et inbecillus. Das angebliche Epikurfragment bei Laktanz, De ira dei 13,20–21, in: Vigiliae Christianae 42 (1988), pp. 47–58

Sextus Empiricus, Outlines of Pyrrhonism, 175: "those who firmly maintain that god exists will be forced into impiety; for if they say that he [god] takes care of everything, they will be saying that god is the cause of evils, while if they say that he takes care of some things only or even nothing, they will be forced to say that he is either malevolent or weak"

Trans. Robert Pinsky, The Inferno of Dante, p. 320 n. 11.

On Goals, 1.65

Epicurus, "Letter to Menoeceus", contained in Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book X

The Story of Philosophy: The Essential Guide to the History of Western Philosophy. Bryan Magee. DK Publishing, Inc. 1998.

Russell, Bertrand. A History of Western Philosophy, pp. 239–40

Epicurus (c 341–270 BC) British Humanist Association

Tim O'Keefe, Epicurus on Freedom, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 134

Epicurus Principal Doctrines tranls. by Robert Drew Hicks (1925)

Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, X, 31.

Principal Doctrines, 24.

Cf. Sallust, The War With Catiline, Caesar's speech: 51.29 & Cato's reply: 52.13).

Letter to William Short, 11 Oct. 1819 in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson : 1816–1826 by Thomas Jefferson, Paul Leicester Ford, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1899

Townhall.com::Talk Radio Online::Radio Show

Anon., Gérald Ghislain—Creator of The Scent of Departure. IdeaMensch, July 14, 2011.Michel Onfray, La puissance d'exister: Manifeste hédoniste, Grasset, 2006Further reading

- Dane R. Gordon and David B. Suits, Epicurus. His Continuing Influence and Contemporary Relevance, Rochester, N.Y.: RIT Cary Graphic Arts Press, 2003.

- Holmes, Brooke & Shearin, W. H. Dynamic Reading: Studies in the Reception of Epicureanism, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Jones, Howard. The Epicurean Tradition, New York: Routledge, 1989.

- Neven Leddy and Avi S. Lifschitz, Epicurus in the Enlightenment, Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2009.

- Long, A.A. & Sedley, D.N. The Hellenistic Philosophers Volume 1, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987. (ISBN 0-521-27556-3)

- Long, Roderick (2008). "Epicureanism". In Hamowy, Ronald. The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Martin Ferguson Smith (ed.), Diogenes of Oinoanda. The Epicurean inscription, edited with introduction, translation, and notes, Naples: Bibliopolis, 1993.

- Martin Ferguson Smith, Supplement to Diogenes of Oinoanda. The Epicurean Inscription, Naples: Bibliopolis, 2003.

- Warren, James (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Epicureanism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Wilson, Catherine. Epicureanism at the Origins of Modernity, New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Zeller, Eduard; Reichel, Oswald J., The Stoics, Epicureans and Sceptics, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1892

External links

This page was last modified on 29 January 2016, at 15:58.

Text is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the

Terms of Use and

Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the

Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.